Category: Short Story

-

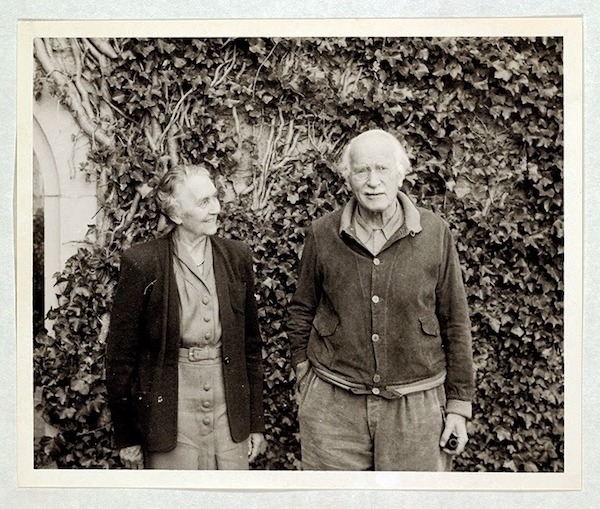

A Famous Couple

Carl and Emma: A Love Story Dearest, I was telling our grandson, Andreas, just the other day, how he possesses the feeling function more strongly than I. He had just espied, while on our walk, a darling dead chaffinch on the ground, and was kneeling over its poor lifeless body. The words, Nothing truly dies…

-

At the Swimming Pool

A Short Story Jeanie is one of these inch worm types. One toe in; one toe back. The cold has always been alien. From birth, really. Even today, with the water temperature around twenty degrees. Babies are gurgling in mothers’ and fathers’ arms in the pool, for God’s sake. Cassius with the lean and hungry…

-

A Fairy Story

Jade was a much longed-for baby. I had waited five years into my marriage before I conceived. I secretly wanted a girl and it was as if a God had heard my silent wish and she’d come to me in my late thirties, drawn by an invisible pull. The experience of being pregnant, of giving…