Definitions

“Culture Shock” is the term for an individual’s surprise, dismay and/or euphoria when first meeting with an alien or different culture.

I experienced culture shock as euphoria, when I first arrived in Paris in the sixties. It’s not surprising that I was amazed at the beauty of the place. So different from Australian landscape, which are beautiful in a diametrically opposed way.

Later on, I found myself in the middle of a revolution. Students were pulling up paving stones in the Latin Quarter and throwing them at the police; barriers were being made from piled-up cars that had been set alight in the streets. I was overwhelmed.

My own brother experienced culture shock, negatively, when he returned to Australia from his adopted country of France, after ten years spent in that almost opposite universe. Even the sight of young boys and girls in uniform, dressed identically, blew him apart. He’d spent his childhood and teens in country Australia then settled and married in France. French customs seemed to highlight and ratify his worst experiences within his own country.

Mum told her friends that her son, at nineteen, had “become an existentialist just like like Jean-Paul Sartre!” From “Bill” and “Billy”, he became “Willy” /weelee/ and “William” /weeljum/.

They’re A Weird Mob

We’re all weird! Countries, and individuals, the lot! How could it be otherwise, we all being part of the human race, that straggledy raggledy collection of stardust, atoms and molecules, in flux like flotsam and jetsom, as if from a dangerous experiment, as we try to reform and turn ourselves into something “other” and better. They’re a Weird Mob is a popular 1957 Australian novel written about Australian customs by John O’Grady under the pseudonym of “Nino Culotta”, the name of the main character of the book. The book was the first published novel by O’Grady, with an initial print run of 6,000 hardback copies. Nino was a fictional Italian immigrant in the fifties, lonely and dismayed by the Australian customs, such as “shout a drink”, meaning to buy a round of beers when it was your turn.

Just off the boat from northern Italy, Nino (Giovanni) Culotta arrived in Sydney. He thought he spoke English but he’d never heard anything like the language these Australians were speaking.

They’re a Weird Mob is an hilarious snapshot of the immigrant experience in conservative Menzies-era Australia, by a writer with a brilliant ear for the Australian way with words. (https://www.booktopia.com.au/they-re-a-weird-mob-nino-culotta/book/9781921922183.html)

Many of our earliest migrants were from Greece and Italy, later on from the former Yugoslavia and Northern European countries. Immigrants often couldn’t speak a word of English and couldn’t rely on free lessons, which only came in the seventies. Australians were not always understanding of the difficulties faced by new migrants. The English were called “Ten Bob Poms”, Italians were “Ities”, and Greeks were “Wogs” and “Dagos”.

Just coming out of the White Australian Era, ours was a conformist society. It is not surprising that many of us “educated Aussies” left for overseas at the end of the fifties.

Refugees to Australia

Today, many refugees experience extreme culture shock when they are sent out to country places in Australia that are different from their native locales. Under our previous governments, we have had a poor record in how we treat such people. With a recent change in government, hopefully, the future will be brighter in this area.

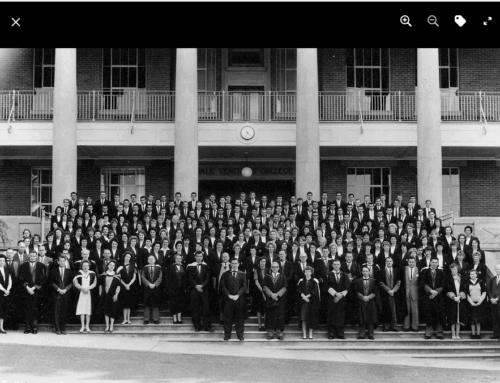

I recently returned for a 60th reunion of ex-students from Armidale Teachers’ College, situated in the western highlands of New South Wales. Did we experience culture shock all those decades ago? Yes, certainly: It was the first time living away from home, and in a colder environment, for many of us. However, we were shielded from the worst effects of loneliness and angst by being housed together in residential colleges along with some of our mates from back home.

While up north, I met a young taxi driver from Iraq. It was cold in Armidale, he said, and everything closed too early, at 2pm. I agreed with him about this. His goal was to learn more English and to go to a bigger centre, such as Melbourne. People were not always friendly in Armidale. He was saving money with escape in mind.

I suddenly had a vivid impression and realization about why my refugee taxi driver had looked so sad. For me, returning to Armidale had been all about meeting up with friends from the past, experiencing pleasure at events and dinners, and visiting the art deco “College on the Hill”, with its majestic setting, Grecian pillars and valuable art collection. All so different from my life in Sydney. This was two faces of culture shock portrayed vividly for me!

Take Away: Here I explore the term “Culture Shock” and provide three or four examples of the phenomenon, and what it implies for the persons experiencing it. This touches on the wider themes of racism, languages and culture, that either include or exclude others who are “different”, from a sense of belonging and from partaking of the advantages of a particular society

Leave A Comment