Sensitivity or Mental Illness?

In our family, I was the overly sensitive one. Recently, I was rated high in intuition, feeling and perception, in a Myers-Briggs personality test. Fate had paired me off with a mother who had quite a thick hide. Small things upset me, and big things were crushing for my very soul. One instance was the near-death of a beloved brother when I was six. I tried to conceal my “weakness”, and took on the guilt for some things that were not my fault. It meant that I grew up carrying heavy emotional baggage on my shoulders: even responsibility for this brother’s accident.

Later on, after much work on my part, I was able to heal from my troubles. I even got rid of the “Black Dog” of depression, so that I could bring up my two children in a healthy environment.

Still much later on, I learnt to have compassion for my mother, who suffered from “nerves” that were misunderstood afflictions in those days. One of my main aims in writing is to destigmatise mental illness.

At the time of my writing, mental illness is still a source of stigma for those suffering from it, and often feared by those who are ignorant about it. Many sporting stars, as well as artists, actors and creative writers are among those attending psychological clinics, who choose not to publicise their affliction.

And yet, more and more books are being written and published, revealing the ubiquitous nature of mental illness in society today. See recent books by Guy Winch, a clinical psychologist with hard-earned wisdom, offering solutions to these questions.

Learning to have compassion

Sometimes I’ve felt like The Idiot in the masterpiece by Dostoyevsky, because I’ve found it hard to give up on those who are suffering. The protagonist, Prince Myshkin, puts up with a lot, and comes across as being stupid; but he is the incarnation of compassion within the structure of the novel. The title is meant to be ironic.

Learning from your own emotional struggles and rejections, is also how you learn to have compassion for others. This often starts in the home. If not, school days usually teach us about this all-important emotion. In fact, it’s often through suffering ourselves, that we learn to have compassion and sympathy for others.

The Power of Words

When I was in fourth class at primary school, my teacher, a returned war serviceman, who’d been wounded in the Second World War, used to write this short poem on the blackboard. It was for cursive writing practice. I was never good at handwriting, but I loved poetry. The sentiments expressed in this poem made a great impression on me at the time.

Life is mostly froth and bubble,

Two things stand like stone.

Kindness in another’s trouble,

Courage in your own.

This sentiment stood by me when I was being bullied at junior primary school around this time; when I felt terribly alone with no one to stand up for me. Many sensitive children go through this at some stage in their school days.

My reaction was in part linked to guilt over the near-death accident of a beloved brother.

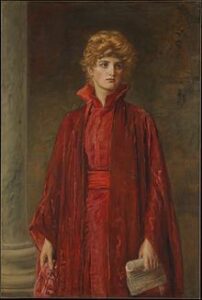

Later on, in high school, Shakespeare’s words attributed to Portia in The Merchant of Venice (the court scene) made a similarly huge impact on me:

The quality of mercy is not strain’d,

It droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven

Upon the place beneath: it is twice blest;

It blesseth him that gives and him that takes’

Tis mightiest in the mightiest; it becomes

The thronèd monarch better than his crown.

His scepter shows the force of temporal power,

The attribute to awe and majesty

Wherein doth sit the dread and fear of kings;

The Merchant of Venice: Act 4 Scene Scene 1

Finding a Mentor and Kindred Spirit

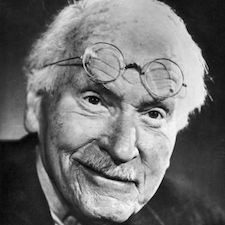

When I first read Memories, Dreams and Reflections by Carl Jung, I knew that I’d found a kindred spirit, or at least, a mentor. Jung’s ideas on Projection have been an especially enlightening idea for me. He claimed that it was the most ubiquitous aspect of human psychology. He even went as far as to say that the best political, social, and spiritual work we can do is to withdraw—that is to reclaim— the projection of our own shadow on to others. As a child, he felt alone, and still felt like that as an adult, and even as an old man. This was because he knew things, and had to hint at things, which others didn’t know about, and for the most part, didn’t want to know about.

When I first read Memories, Dreams and Reflections by Carl Jung, I knew that I’d found a kindred spirit, or at least, a mentor. Jung’s ideas on Projection have been an especially enlightening idea for me. He claimed that it was the most ubiquitous aspect of human psychology. He even went as far as to say that the best political, social, and spiritual work we can do is to withdraw—that is to reclaim— the projection of our own shadow on to others. As a child, he felt alone, and still felt like that as an adult, and even as an old man. This was because he knew things, and had to hint at things, which others didn’t know about, and for the most part, didn’t want to know about.

Today, we are often tarred with the title of “whacko” if we hint at our own personal experiences that seem to collide with or question accepted social tenets, especially those of traditional notions of Science today. Carl Jung in the early twentieth century knew this, and kept many of his thoughts to himself.

Even the great Russian writer, Tolstoy, in the nineteenth century, succumbed to depression in later life, and could not hold onto his religious beliefs, which had nonetheless inspired an exalted community of followers, including Mahatma Gandhi. In his Confessions, written in late middle age, Tolstoy expresses his disillusionment with religion, and turns to a more mystical/Eastern search for God. He was excommunicated by the Orthodox church in response to expressing his true opinions.

Yes negative feedback can be highly destructive to all writers, not only the ‘sensitive’ ones. The worst feeling is being misunderstood, and judged on criteria that simply don’t apply to one’s genre. I employed a structural editor who showed in her first few comments that she simply didn’t ‘get it’. Wasting no time on self-pity, I immediately found an editor who was empathetic, intelligent, and gave constructive criticism. Worth persisting, but only with the right editor.

Yes, great advice from someone who knows, Dina! With a little time and hindsight, I’m now able to get on with making the positive changes to the text that were suggested, without over-reacting and changing the whole story too much. I wish I had some of your chutzpa. Sensitivity is a must for the creative writing process, but editing and getting published often require almost opposite skills.