Way back then, at Armidale Teachers’ College, Liz was reminiscent of one of those Botticelli angels, but without the curls. She looked a lot like Miranda from Picnic at Hanging Rock. Able to attract the attentions of the college Adonis at the time, ideal partner for an Aphrodite, she did so without vanity, without affectation. I remember her telling me that her mother had died when she was younger. My mother was alive, but there were issues. And my immaturity translated itself into a political conversion to Communism during my college years. Could it solve the world problems of inequality, the scurge of warring nations? I even travelled from France to the USSR after Teachers’ College, to try to find out the answer to this.

Only in recent years, since the College Reunion in 2011, have Liz and I become close friends. Our common experiences of having lived and worked in France was one of the triggers.

She still has that angelic quality about her, but it is one that incarns wisdom now, rather than mere surface features.

We met in May at the Sydney Writers’ Festival this year. It has grown bigger each year, and the multiple venues are more comfortable and containing than before. Many sessions are free or inexpensive and easily accessible.

Liz chose the talk by Robert Dessaix: “On Kissing, Hugging and Saying ‘I Love You'”. I valued her judgement and went along with it. We were not disappointed.

Liz chose the talk by Robert Dessaix: “On Kissing, Hugging and Saying ‘I Love You'”. I valued her judgement and went along with it. We were not disappointed.

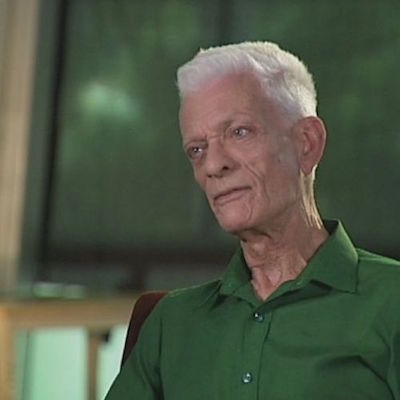

“An orgy of kissing and hugging has broken out across the Western world”, Dessaix proclaimed in his satirical monologue, “and we have to take a stand”.

He kept us enthralled by his erudite, funny and poetic sentences, with lots of modern references, as well as allusions to Russian writings, such as Alexai Pushkin’s poem, “I Loved You”.

Typical of his ironic stand is when he noted that the liver is the organ to represent romantic love in Java, not the heart.

The high point for me was, while Liz was seeking out a political event, to happen upon a talk by a young American French woman, Nadja Spiegelman. Her talk about her memoir, “I’m Supposed to Protect You From All This”, I wouldn’t have missed for the world! I bought the book and read it greedily.

The author is the daughter of a French woman and an American father, both well-known writers. The memoir traces four generations of mothers and daughters, from Paris to New York and back again. It is the story of strong French women who survive the war and battle against the patriarchal values of the times in France. The young author—she is twenty-seven years old—tells an archetypal story that all women could relate to in its universality, about jealousy and pain, often passed on to daughters, who often have to survive or resist their mothers’ stories. Françoise, the mother of the author, survived her background by emigrating to America. This memoir also recognises the truth of the fallibility of memory.

The author is the daughter of a French woman and an American father, both well-known writers. The memoir traces four generations of mothers and daughters, from Paris to New York and back again. It is the story of strong French women who survive the war and battle against the patriarchal values of the times in France. The young author—she is twenty-seven years old—tells an archetypal story that all women could relate to in its universality, about jealousy and pain, often passed on to daughters, who often have to survive or resist their mothers’ stories. Françoise, the mother of the author, survived her background by emigrating to America. This memoir also recognises the truth of the fallibility of memory.

Angels, the kind without wings of course—magical women—inhabit this book. Their stories and voices will remain in the reader’s mind for a long time, given the writer’s artful use of language and her enviable communication skills.

The beginning sentences are marvellous: “When I was a child, I knew that my mother was a fairy. Not the kind of fairy with gauzy wings and a magic wand, but one with a thrift-store fur coat and ink-stained fingers.”

Other gems are: “Pure memories are like dinosaur bones…discrete fragments from which we compose the image of the dinosaur…But memories we tell as stories come alive. And when we look again, our memories are whole, breathing creatures that roam our past.”

Editor’s note: Thanks to Ian Wells for pointing out my incorrect use of the word “infallibility” above. I meant the opposite. Each mother/daughter in this memoir has a differing perspective on their past relationships and contradictory memories of similar events. I’ve now changed the word to the “fallibility” of memory.

The memoir emerged from Nadja’s own questions about the conflicting versions of family stories. Who decides what the truth is? Who owns a story? It’s these questions that Nadja wanted to explore. “Within families there often isn’t any kind of historical record, but there often is a real battle for who has the truth.”

Nadja and her mother, Françoise Mouly

I often write of my past. I cherish reminiscing. Each exercise’s creation is celebratory; a way to eulogize the beauty of my life and my memories of it.

Sorry Anne, but I have to take exception to your statement, “This memoir also recognises the truth of the infallibility of memory”.

I know from personal experience that two people who share an experience can later have different memories of it. Memory is far from infallible. It is easy to manipulate memories. One of the major researchers in this field is Elizabeth Loftus. Studies show memories are fugitive (i.e. fade over time) or modifiable over time through the effects of newer experiences. Our memory is never truly true or really real. Instead it’s just a partial recollection of something that happened in the past, we didn’t probably see or know the full truth when it happened in the first place. And we unknowingly introduced additional inaccuracies when we interpreted it, stored it and retrieved it. You can see this clearly in criminal trials when eye witnesses all honestly give different versions of their truth.

All we can do is pass on or record our memories, perhaps as memoirs, and leave an interpretation of what (we think) happened.

Never-the-less I of course enjoyed reading SERENDIPITY AT THE 2017 SYDNEY WRITERS’ FESTIVAL, as I have done with your earlier creative forays and look forward eagerly to reading more soon.

Right/write on!

Thanks for pointing this out, Ian. it’s a mistake: I meant fallibility, of course. Each mother/daughter pair in this story have differing memories of the same event/s. I’ll change it now. Thanks for your comment and the additional information re Elizabeth Loftus.