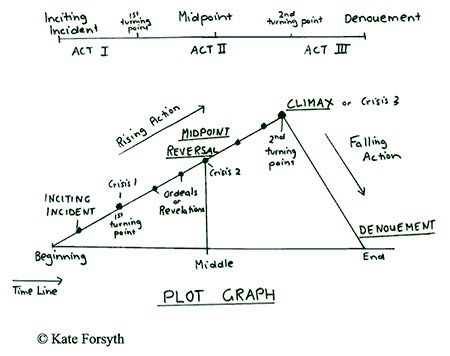

Note: I first published this post on this blog in February, 2013. I have added little to the original for re-scheduling it in April 2019, apart from photos and some minor formatting changes. I have also added Kate Forsythe's more complex pyramid diagram below.

How do you go about writing a short story? You might have a good idea and an interesting character to portray, but you have no idea about how to create a valid structure. It’s a bit like building a house, or a bridge: you want to create a solid foundation, sturdy walls and a ceiling. It’s the same for story writing. But you may decide to focus on the final structure at a later stage of production, rather than at the outset. The basic structure is:

A: a Beginning

B: a Middle and

C: an End.

Aristotle first stated this in 350 BC. Just as you can break the parts of a building down into smaller parts, a narrative structure can also be broken into smaller segments that support and fit into the larger framework.

One way of analysing the structure is to think in terms of a seven-point plan. Why seven? This has esthetic connotations, and possibly spiritual ones, too.

The main part of the Introduction is the hook: a focus that motivates the reader’s interest and involves a character facing a problem. The Middle of the story is the meaty part that contains the plot line or sequence of events. Finally you have the Ending, which involves resolution and/or validation.

I am not suggesting that you, as a writer, must always plan your story ahead of time according to this structure. This is not my intention at all, nor my own way of going about writing a short story. You must be allowed to allow the creative juices to flow from the outset. The 7 point structure may help you merely after “getting it down”, to rearrange and to add parts that have been left out of your narrative.

A: The Hook: 1

The Main Character is portrayed in the Introduction as a personnage of interest. There may be a reference, at least implicitly, to a problem linked to the protagonist, who is often good but flawed or different from the personnage we find at the end of the story. The Setting can be included as part of the Introduction.

B: The Plot: 2

The storyline and sequence of events belongs to the Middle Section, and is the longest part of the book. Here the main character is faced with a problem and a call to action. The first attempt is a reactive one and ends in failure.

Reversals of fortune, Recognitions: 3

Pressure is placed on the protagonist to solve the problem and he makes several attempts to do so.

The Midpoint: 4

The protagonist makes an irreversible decision to take decisive action despite fears and overwhelming obstacles.

Things Worsen: 5

Despite the well-meaning actions of the protagonist, actions may even be the cause of reversals in fortune. At the same time, learning takes place. The character is henceforth prepared and ready for resolution.

C: Extreme Deterioration: 6

At the end comes climax: the character tries to resolve the problem once again and either fails or succeeds in the end. It’s important that the protagonist doesn’t give up, either way. We feel pity and fear for the hero and hope for success.

Resolution: 7

Validation shows that the story is over. The ending validates the promise set up in the beginning. Or it may overturn or reject it.

Addendum:

Keep the basic structure of Introduction, Middle and End in the back of your mind while getting your story down. You may be able to create an esthetic whole straight off. Editing drafts to perfect it may be all that is needed.

If not, rearrange and “flesh out” your story according to the above more complex guidelines. This can be done “after the event”, that is, during the second and successive drafts of the narrative.

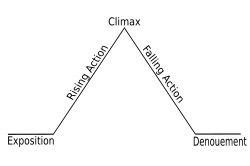

Gustav Freytag in 1900 further developed Aristotle’s ideas by his pyramid diagram with its 7 points:

Leave A Comment